Bath Cycling Club Gazette

In the number of February 1911 of the journal named at the head of this note the following account initialled N.C.H. appeared:

An African Experience

"Now you quite understand, H? Captain X must have this before midnight. It's not safe to travel by daylight. Go at sunset. You had better take the machine - it's quieter than a horse. Travel light. Take a Mauser pistol instead of the rifle, you know the road and it's only twenty-seven miles. Be careful at Rhenoster Spruit. Good luck! You needn't hurry back."

Such were my instructions one evening just before sunset on the South African veldt.

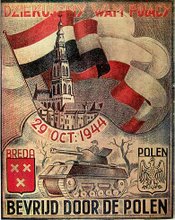

The Boers had been making themselves unpleasant to a large convoy, and were now traveling back in small detached parties up the valley where we and several other troops were stationed. I had to take a message (and my chances!) to our next nearest post 27 miles off. The sun set at 7:30; fifteen minutes later out there it would be dark, but the moon was due up somewhere between ten and eleven, and I reckoned that if I left about 8 o'clock this would find me somewhere in the vicinity of Rhenoster Spruit, about eighteen miles on the way. This was a nasty spot, even in daylight, the banks on each side almost as steep as a house and on all sides thick bush and boulders.

Just after eight o'clock I pushed the machine (we had two of them in the troop - khaki-coloured Raleighs) over the veldt from our post to the main road, or track, down the valley - a faint streak by night, with waterworn wheel-ruts over two feet deep in places, patches of loose sand and stones which meant 'full stop' once you rode into them. The only safe way was to follow a native's foot track as it wound its way over the road, sometimes on the left, sometimes on the right. It was a by no means easy task in daytime, but ten times worse at night without a lamp, for I feared much under the circumstances to have a light - in fact, I knew it would be almost fatal to advertise my presence by its tell-tale glimmer. A whispered "So long" to the outpost on the roadside, and I was in the saddle, and soon swallowed up in the African night.

One's senses, if one loves the veldt and the mysterious indescribable vastness of "the wild", soon become acute and seeem to work independently of the brain. It was some such sense that suddenly pulled my thoughts back to my machine and the duty before me. I had covered about sixteen or seventeen miles and the time was just 10 o'clock. The night was still very dark (indeed, I had already had half-adozen spills, charging pot holes or boulders on the road), when I felt the unpleasant sensation, the first time since my initial lonely dispatch ride nearly four months previously, of wanting to look behind me.

Another half-mile, and I dismounted, listening with every sense at the highest tension. Not a sound. With the thoughts of Rhenoster Spruit in front of me, I carefully felt over the machine, gingerly pumped up the tyres, and after another minute's careful listening, with bated breath, got going again.

It could not have been more than a hundred and fifty yards from the actual spruit bottom when the moon sent her first ray of light over the tops of the Magalies berge, and saw me let the machine roll slowly over to the left while I flattened myself on the roadside. Once more that creepy feeling of wanting to look behind me, and a sensation of hair standing on end, assailed me, five, ten fifteen minutes went by, and I still could not bring myself to ride through those bushes and down the banks of the spruit. I did not know the condition of the banks above or below where the actual track crossed the spruit, and to swim was out of the question, as I had the machine. Another five minutes, and I decided to creep towards the bank downstream and look for a crossing. Working my way carefully in a diagonal direction, I was lucky to find a safe, but rocky crossing, within a few yards of the spot where I had struck the spruit.

A loose stone and a stumble caused me a wetting up to the waist. One counts a wet shirt but little when dispatch riding, however, and I was soon clambering up among the bushes of the steep bank and working my way towards the track again, and within a quarter-of-an-hour of my wetting was once more pedalling towards my goal, laughing to think how superstitious I had been to funk the proper ford.

Twenty yards - perhaps fifty - had been covered, when the sudden double report of a Mauser rifle made me almost leap out of the saddle, and a faint, ghostly flake of white on the track a little ahead of me shewed where a bullet had struck. I made a hasty dive for the first cover I could find, swore at the moonlight, and then looked back.

It was difficult to locate the exact spot from where the firing came, but I had little doubt the position had been chosen to cover the ford.

After firing a couple of clips full of cartridges from the Mauser pistol at what I thought would be the position of the ford, I mounted as fast as I could and cleared. A few more shots shewed that I was seen, but the bullets must have been very wide, for I did not even hear them sing anywhere near me.

There is little more to tell. My front tyre had a bad burst when camp was reached, and from the look of the rim I must have done half the remaining distance with the tyre flat, but I had no recollection of it. A patrol party next morning found the footprints and cartridge cases of at least three Boers in a snug corner commanding both slopes down to the Spruit. I'm thankful now that I cycled instead of taking a horse, and I'm also very glad that my hair did stand on end before I attempted to cross that spruit the usual way!"

N.C.H. stand for Major Noel Cambridge Harbutt whose obituary appeared in the Bath Weekly Chronicle & Herald on 5 November 1949. In the South African War he served with the Somserset Light Infantry and later with the S.A. Constabulary under Baden-Powell. He was the son of the inventor of plasticine and chairman at the time of his death of Harbutt's Plasticine Ltd., Bathampton. With these interesting notes as a gift to the Africana Musuem came two albums about the S.A. Constabulary with private photographs by Major Harbutt who was an A.R.P.S. There was also a felt hat of the S.A.C. very similar to that used by the Boy Scouts.

From: AFRICANA NOTES AND NEWS / AFRICANA AANTEKENINGE EN NUUS, VOL. 21 1975, PP. 337-9

Thomas Eakins' John Biglin in a Single Scull, 1874, is a masterpiece. Our rower is placed directly in the middle of the canvas, body and boat forming the triangle so common in classic portraiture. The horizon meets his concentrated brow, and his arm and oar echo the equilateral triangle of man and vessel with an isosceles. Beyond Eakins' formal mastery, his efforts to render reflections are borne out wonderfully in this piece, about which Robert Hughes states, "...the arrowing interweave of reflections below the boat, containing the colors of the varnished hull, Biglin's white singlet, his skin, and his red sweat-bandanna, seem to have the beauty of undeniable fact-a fact, however, which we cannot test for ourselves, but induced to take on trust." American Visions, pg. 291.

Thomas Eakins' John Biglin in a Single Scull, 1874, is a masterpiece. Our rower is placed directly in the middle of the canvas, body and boat forming the triangle so common in classic portraiture. The horizon meets his concentrated brow, and his arm and oar echo the equilateral triangle of man and vessel with an isosceles. Beyond Eakins' formal mastery, his efforts to render reflections are borne out wonderfully in this piece, about which Robert Hughes states, "...the arrowing interweave of reflections below the boat, containing the colors of the varnished hull, Biglin's white singlet, his skin, and his red sweat-bandanna, seem to have the beauty of undeniable fact-a fact, however, which we cannot test for ourselves, but induced to take on trust." American Visions, pg. 291. Skating, perhaps, but only if you're in the Netherlands and it's wintertime and the canals actually freeze over, which they have not done in the last ten years in any appreciable way (right, The Skater (Portrait of William Grant), Gilbert Stuart, 1782). Rollerblading is nice, though not in the winter, where cross-country skiing is great (The usefulness of skiing is to be seen in the awesome Finnish decimation of platoon after platoon of Russian invaders during WWII). But cross-country skiing is limited to winter, which only works for half the year in certain snowy countries. And so we are left with the bicycle, useful all year round.

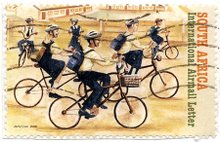

Skating, perhaps, but only if you're in the Netherlands and it's wintertime and the canals actually freeze over, which they have not done in the last ten years in any appreciable way (right, The Skater (Portrait of William Grant), Gilbert Stuart, 1782). Rollerblading is nice, though not in the winter, where cross-country skiing is great (The usefulness of skiing is to be seen in the awesome Finnish decimation of platoon after platoon of Russian invaders during WWII). But cross-country skiing is limited to winter, which only works for half the year in certain snowy countries. And so we are left with the bicycle, useful all year round.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)